Taiga Plant Adaptations

The taiga, also known as the boreal forest, is one of the world’s largest biomes (the largest terrestrial biome) in the sub-arctic region (lies just south of the Arctic Circle), stretching across northern regions of North America, Europe, and Asia. It is characterized by harsh winters, short growing seasons, and nutrient-poor soil.

The taiga biome spans regions like Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, and Siberia. In Russia, the taiga covers an immense area, stretching approximately 5,800 kilometers (3,600 miles) from the Pacific Ocean to the Ural Mountains.

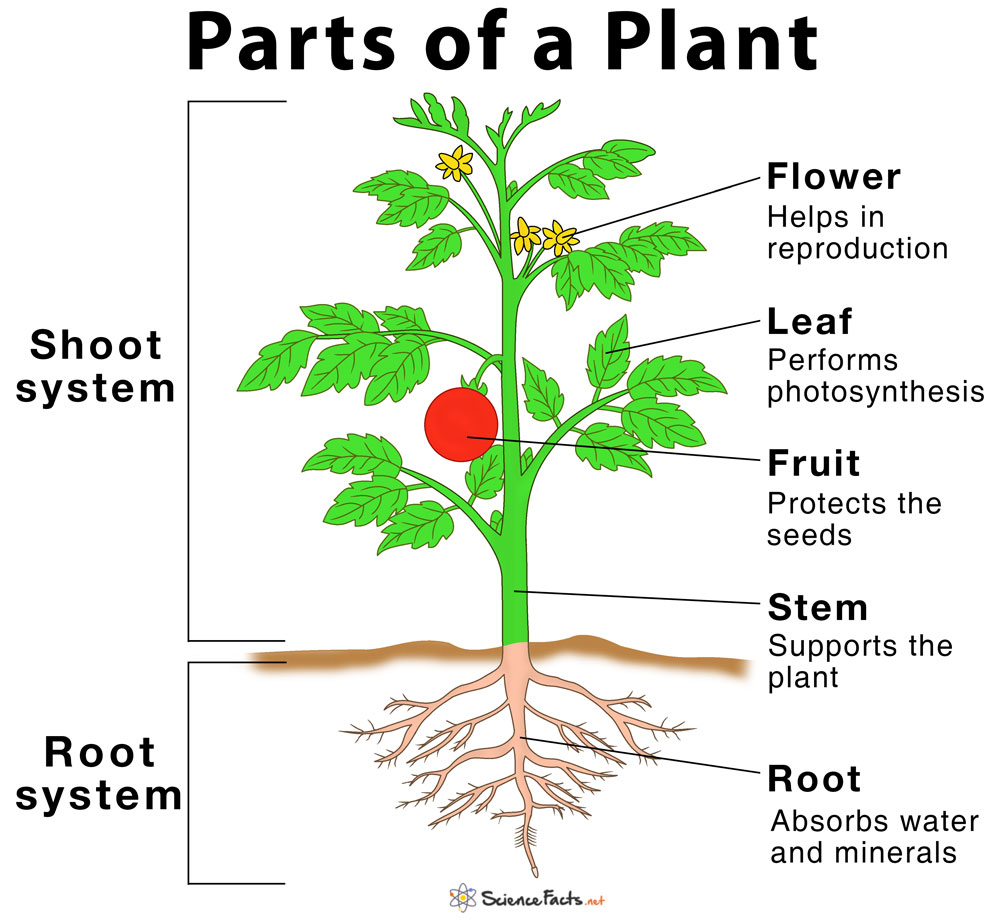

To survive in such extreme conditions, plants in the taiga have developed some key adaptations:

Dark-Colored and Needle-Like Leaves

Most of the plants in the taiga, including spruce, pine, and fir, have modified their leaves into spines to reduce water loss by transpiration. These leaves also contain fewer stomata (pores for gas exchange) and retain very little moisture, which helps prevent them from freezing.

The waxy coating in the leaves further helps their cause. Their narrow shape minimizes surface area, preventing snow accumulation and damage during winter. Additionally, the dark green color helps absorb maximum sunlight for photosynthesis during the short growing season.

Dark-colored leaves in the taiga are an adaptation that helps plants maximize sunlight absorption in the harsh, low-light conditions typical of this biome. This adaptation is especially critical in the taiga, where the sun’s angle is often low, and days are shorter. By absorbing more light, dark-colored leaves support efficient photosynthesis, allowing plants to produce the energy needed for survival in cold and nutrient-poor environments.

Conical Shape

Many coniferous trees like Larch and Norway Spruce have a conical or triangular shape. This unique structure helps them shed snow easily, preventing branches from breaking down. The sharp, pointed top also allows them to withstand strong winds.

Evergreen Nature

Most trees in the taiga are evergreen, retaining their spine-like leaves almost throughout the year. This adaptation allows them to begin photosynthesis as soon as conditions are favorable without needing to regrow leaves. By staying green year-round, they maximize energy production during the limited sunlight available.

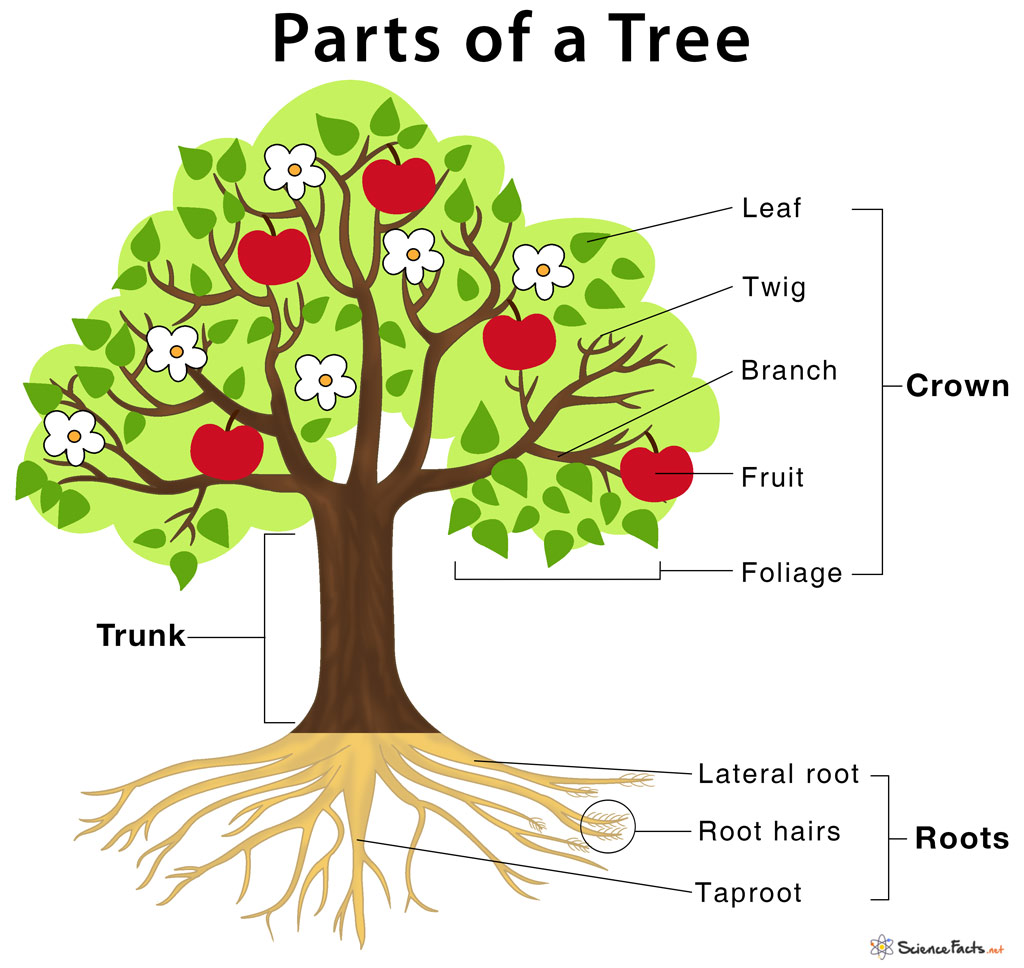

Shallow Root Systems

The soil in the taiga remains frozen year-round, with a layer of permafrost in some regions, and thus, it is nutrient-poor. To adapt to such a condition, plants have shallow but wide root systems that spread horizontally just below the surface, enabling them to anchor themselves and absorb nutrients from a thin soil layer.

The taiga forest floor is dominated by mosses, lichens, and mushrooms rather than shrubs or flowers. These organisms thrive with minimal root systems or by growing directly on the soil’s surface.

The larch stands out as one of the few deciduous trees capable of thriving in the harsh, freezing conditions of the northern taiga.

Thick Bark and Flexible Branches

Many taiga trees have thick bark, which acts as insulation against freezing temperatures and protects the inner layers from damage. The bark also defends against fire, which, although rare, can occur during dry seasons.

Hardwood trees that manage to survive in the boreal forest have developed unique adaptations to handle the weight of heavy snow. For instance, birches and aspens possess flexible branches that can bend under snow, preventing them from snapping.

Many boreal trees have adapted to survive and thrive in fire-prone environments. Species like jack pine and black spruce rely on a trait called serotiny, where intense wildfire heat is needed to open their cones and release seeds. Other trees, such as aspen, birch, and balsam poplar, quickly regenerate after fires by sprouting from roots or dispersing lightweight seeds over vast areas. Plants like fireweed also play a role in recolonizing burnt tracts.

Seed Adaptations

Seeds of taiga plants are often housed in cones, protecting them from the cold and predators. Conifers produce large quantities of seeds to ensure successful reproduction, even in unfavorable conditions.

Slow Growth Rate

Due to the nutrient-deficit soil and short growing seasons, plants in the taiga have a slow growth rate. This adaptation conserves energy and allows trees to live for hundreds of years despite the challenging conditions.

Symbiotic Association

Many taiga plants, such as conifers and members of the heath family (Ericaceae), form symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi on their roots. These fungi enhance the plant’s ability to absorb nutrients from the nutrient-poor soil. In return, the plants provide the fungi with sugars produced during photosynthesis, creating a mutually beneficial relationship.

-

References

Article was last reviewed on Tuesday, December 3, 2024