Electric Field

What is Electric Field

An electric field is an invisible force field caused by an electric charge. It is an alteration in the space (air or vacuum) around the charge. It results in an electric force that is felt by electric charges when placed close to one another. A static electric field is created when the charges are stationary, and the corresponding force is known as electrostatic force. The electric field is a vector quantity having both magnitude and direction.

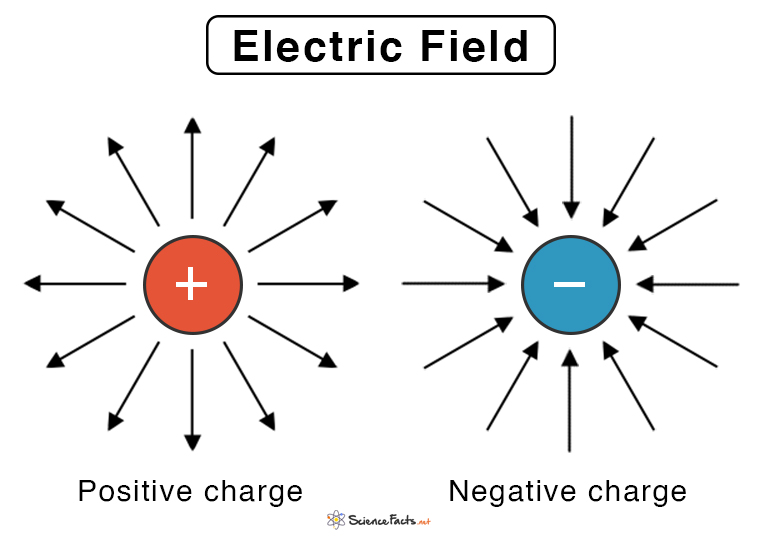

Electric Field Lines and Direction

The strength and direction of the electric field are represented by electric lines of forces or electric field lines. They are imaginary lines drawn around a charge, the tangent at which gives the electric field vector. The lines are drawn with arrows to signify the direction. When a positive charge is placed close to a negative charge, like an electric dipole, the lines come out of the positive charge and terminate into the negative charge. Therefore, the direction of the field indicates the direction towards which a positive charge moves when it is placed under the influence of another charge.

Electric Field Flux

The flux of an electric field is defined as the number of field lines passing through a certain area in space. The area can represent a regular or irregular surface through which the lines pass. Mathematically, it is the dot product of the electric field and the area vector. The symbol ø denotes flux.

If the electric field and area vector makes an angle θ, then the equation is given by

Electric Field Equation

The strength of the electric field in the space surrounding a source charge is known as the electric field intensity. Mathematically, an electric field is defined as the electric force experienced by a unit charge. The following equation gives the electric field vector.

Magnitude of Electric Field

The corresponding scalar equation gives the magnitude formula.

Where,

E: Electric field

F: Electric force

q: Electric charge

SI Unit: Volt/meter (V/m) or Newtons/Coulomb (N/C)

Dimensional Formula: [M L T-3 I-1]

How to Find Electric Field for a Point Charge

The electric field can be calculated using Coulomb’s Law. According to this law, the electric force between two point charges is directly proportional to the product of the charge and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Where,

q1, q2: Magnitudes of the two charges

r: Distance of separation between the charges

εo: Permittivity of free space (= 8.85 x 10-12 C2N-1m-2 or epsilon naught value)

By definition, the electric field is the force per unit charge. Therefore, q1 = q and q2 = 1.

Then, the electric field is given by the following equation.

Thus, the strength of an electric field depends on the magnitude of the source charge.

2. Gauss’s Law

The electric field can be calculated by another method. Gauss’s Law is applied to find the electric field at any point on a closed surface. According to this law, the electric flux through any closed surface is proportional to the total electric charge enclosed by this surface. Mathematically, the law states that the electric flux is the integral of the dot product between the electric field and an infinitesimal surface area.

Using Gauss’s Law, the electric field can be calculated for the following cases:

- Sphere

- Cylinder

- Current-carrying Wire or Line Charge

- Circular Disc and Ring

- Infinite Plane/Sheet

- Parallel Plate Capacitor

- Electric Dipole

- Coaxial Cable

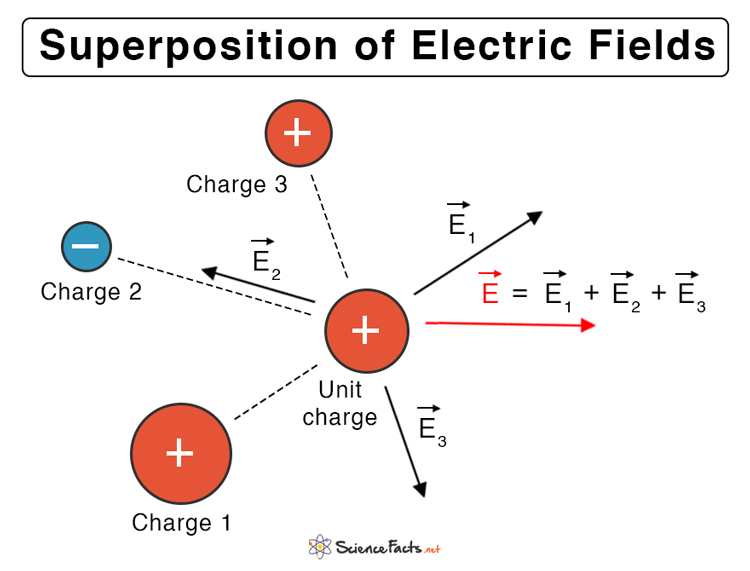

Superposition of Electric Fields

Like all vector fields, the electric field follows the principle of superposition. The net electric field due to a group of charges is equal to the vector sum of the fields created by each charge.

Where

Types of Electric Field

Electric field lines are of two types.

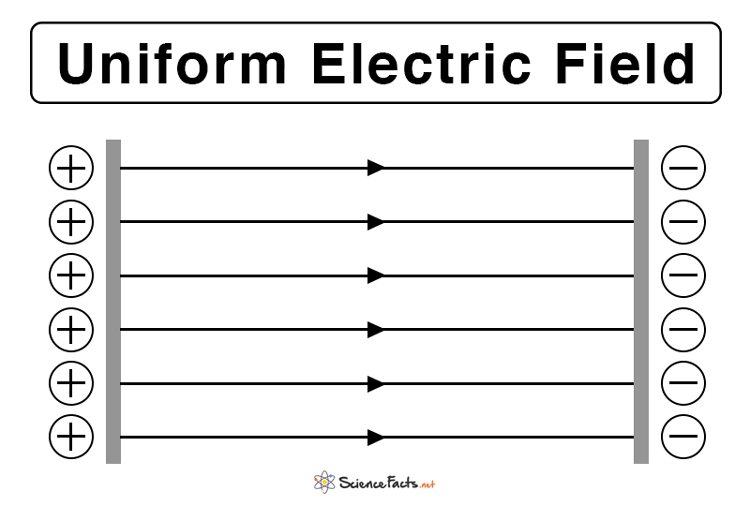

1. Uniform Electric Field

The electric field is said to be uniform if its value remains constant over a region in space. Its magnitude does not depend on the displacement, and the field lines are parallel and equally spaced.

Example: A uniform electric field can be created between two charged parallel plates, also known as a capacitor. The electric field lines come out of the positive plate and terminate in the negative plate.

2. Non-uniform Electric Field

The electric field is non-uniform if its value does not remain constant over a region in space. In this case, the electric field lines are not parallel.

Example: The field generated by a point charge is radial, and its strength is inversely proportional to the distance.

Work Done by an Electric Field

When the test charge is brought closer to the source charge, work has to be done to displace it from one point to another. For example, when a positive charge is brought closer to another positive charge, work is done to overcome the repulsive electric forces.

By definition, work done is the dot product of the force and displacement. The work done by a uniform electric field E in moving a charge q through a distance d is given by,

If the field and the displacement are in the same direction, then

And

The quantity ΔV is known as the potential difference or voltage. It gives the change in potential energy when a unit charge moves from one position to another in the presence of an electric field. Therefore, the work done by an electric field is

How to Find the Work Done by the Electric Field Due to a Point Charge

The electric potential due to a point charge q is given by,

Suppose a charge moves from a position that is at a distance r1 from the source charge to a distance r2. Then, the change in potential energy, which is the work done, is given by

Examples and Problems

Problem 1. An electric force of 8 N is acting on the charge 3 μC at any point. Determine the electric field at that point.

Solution: Given,

F = 8 N

q = 3 μC

Therefore,

E = F/q = 8 N/3 μC = 2.67 x 106 N/μC

Problem 2. A small charge, q = 4 mC, is found in a uniform electric field E = 3.6 N/C. What is the force on the charge?

Solution: Given,

q = 4 mC

E = 3.6 N/C

F = qE = 4 mC x 3.6 N/C = 14.4 mN

FAQs

Ans. When an insulator or a dielectric is placed in an electric field, the electric field strength decreases.

Ans. The electric field inside the conductor is zero because the free charges reside on the surface.

Ans. The electric field can never be negative. It represents a physical quantity, like gravity.

Ans. Electrons move in a direction to an opposite field.

Ans. A changing electric field induces a magnetic field.

Ans. The electric field between two parallel plates usually is parallel. However, at the edges, they curve, meaning that the electric field is greater than in between the plates.

-

References

Article was last reviewed on Friday, February 17, 2023